Mari Andrew, Author of "My Inner Sky”

Photo: Christine Han Photography

There’s something about Mari Andrew—and that something is her beautiful, unrestrained vulnerability. Mari started her highly successful Instagram of illustrations matched with highly specific observations and relatable feelings in 2015 when she was simultaneously stricken with an autoimmune disorder, grieving the death of her father, and going through a breakup. Mari’s approach to healing through opening has resonated with so many people—including me—and it’s led her to publish two books, one of which just came out this month.

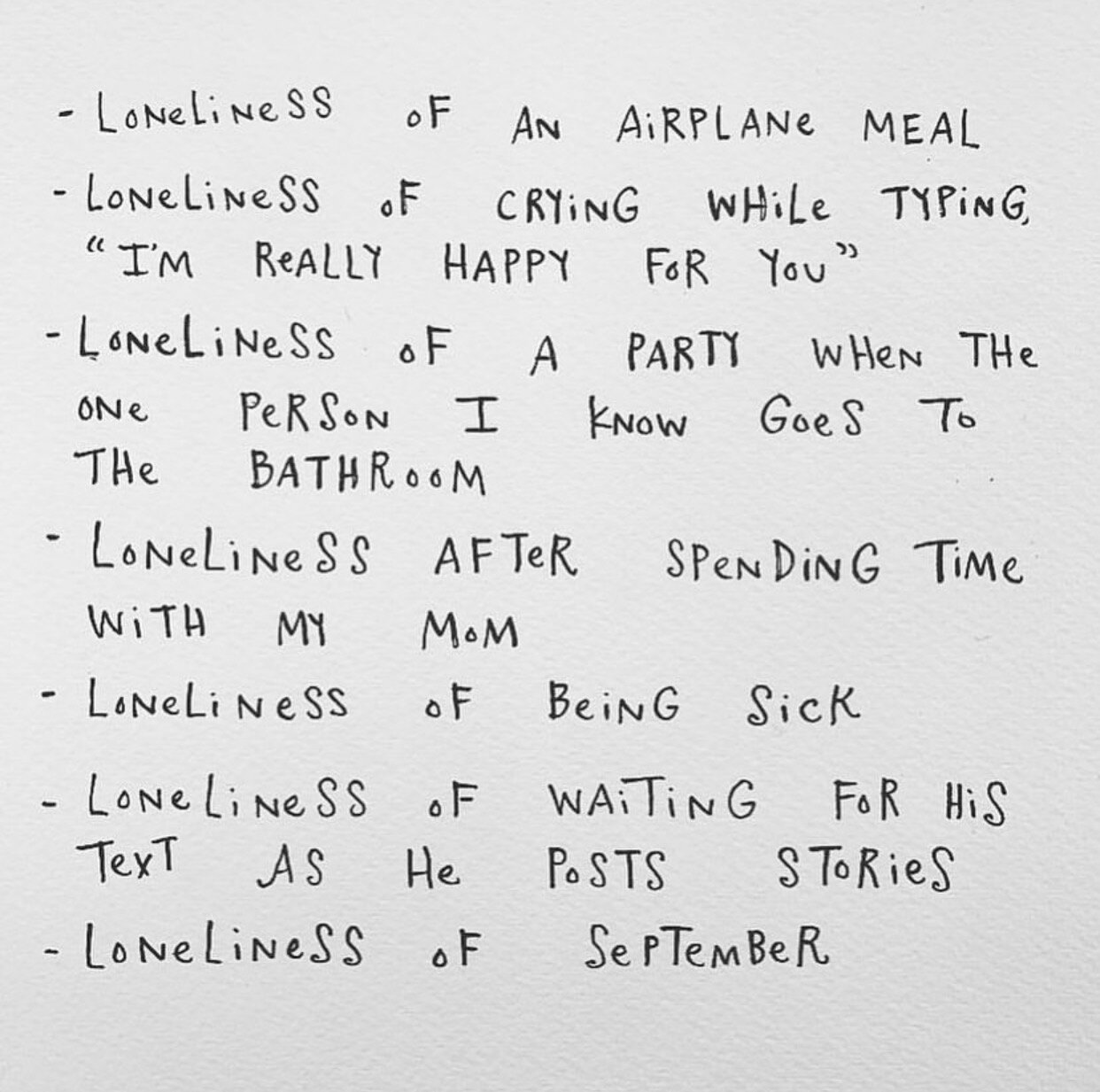

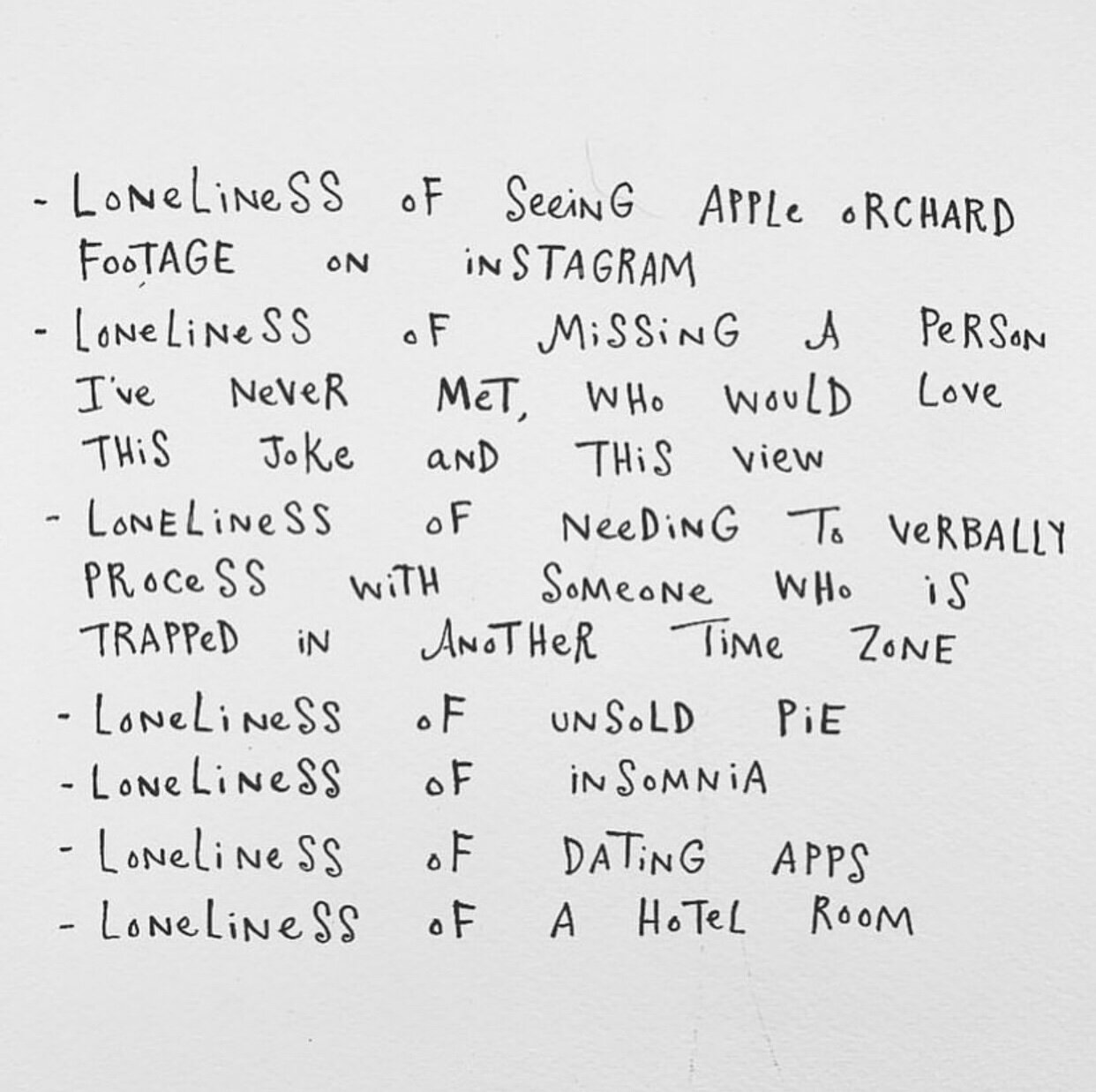

My Inner Sky is a book of heartbreakingly incisive essays shaped around Mari’s ability to reframe the seemingly negative experiences in order to become even more tender, more free. From deep heartbreak over a two-week relationship to the societally and biologically imposed pressures of dating in your 30s and the wavering feels of loneliness and freedom while traveling alone, My Inner Sky is a paean to savoring the small details, feeling all the feelings, and letting your experiences become the source of your strength.

We spoke to Mari about the bright side of hitting rock bottom, the different societal expectations of men and women in relationships, giving ourselves permission to feel the “in between” feelings, and so much more.

Hi! How’s your day?

Good! It’s really surreal; I published a book a few years ago and I remember it was such a pleasantly hectic day running around the city, and now I’m just kind of in my house, isolating. But what else is new!

Well, if it’s any consolation I read your new book My Inner Sky and absolutely loved it. It’s like an elegy for living with acute sensitivity. It really resonated with me.

Thank you so much! I started writing it three years ago and forgot what it was about. And then just this week, I've been thinking like, ‘Oh, my gosh, what did I write in here? Is anyone going to resonate?’ So it’s really nice to hear.

When you’re doubting yourself, do you ever think about how far you’ve come?

I think it's human nature to get accustomed to wherever you are in life. So it’s not so much that I can look back and say, ‘I've come so far in my career,’ because there's so many things I still want to do. But I do feel that way when I look back on certain themes that I wrote about in the book and think, ‘I would really think differently about that now’ or ‘wow I’m truly over that guy.’

When you started writing your first book: “Am I There Yet?“ that came out in 2018, you were grappling with Guillain–Barré syndrome, which left you paralyzed for two years. You mentioned that during that time, you realized that in order to become the person you always wanted to be, you just had to do the things that person would do, i.e. start to regularly draw and write. Can you speak to conquering these fears?

At the time when I began, I didn't have any fear because I felt like the worst thing that could happen to me already did. I started about two years before I found out about my illness, while in the midst of grieving the passing of my dad. I was also going through a breakup and struggling with career lows, just getting rejections left and right. Rock bottom is an amazingly fearless place to be, because you're already at the bottom--you can't fall any further. I just thought, ‘I have to express myself in order to get through this,’ and since other people's expressions have helped me so much in my own life, maybe I can offer that to other people. It was such a creatively lush time for me, and then two years later I got very sick and my hands were paralyzed for six months. So that was a very humbling experience after I felt like I'd really found myself.

Wow. And in your new book “My Inner Sky“, you have an essay about dating this guy “Dave” and you talk about how right before dating him, you finally came to love yourself--was this before the paralysis?

So I moved to New York when I was sort of fully physically recovered in 2017 and I’ve been dating in New York ever since. “Dave” was a story about someone I dated for two weeks that just totally crushed me. I'd never come across a story about someone who was so affected by a two-week relationship, and I thought I need to write this, because someone out there will understand.

I did! It’s the level of connection and not the length of time. In that essay, when you are recounting the breakup, you said something that is so relatable--which is along the lines of “I did the self-work and I love myself now, so isn’t he supposed to show up when I finally do?” When women who are self-critical end up doing “the work” it feels like we create this expectation from the universe, like there's some spirit that's supposed to know when to send you this person. Are you still grappling with that?

It’s a different story every day. But yeah, I think that narrative is really frustrating for a lot of reasons. One is that I don't see men being told the same story. I don't see men being told to work on themselves. When a woman goes through a break up, she's often told “invest in yourself and do things to love yourself more” and men are encouraged to just keep dating. It’s almost like there's an entitlement men have—societally-speaking—to love whenever they want, while women are supposed to “work on themselves” and be their best selves before they can find love. And then when we do all that work, it’s like, ‘Wait, where's the reward? I was told that if I did all these things, I'd get this magical cosmic reward, which is a boyfriend,’ which isn't even really a reward. A relationship is a lot of work. It’s a tremendous growth experience and we treat it like the lollipop you get at the end of all this self-care, which really frustrates me.

And you know when you break up with someone, people often ask “How long were you together?” If it's under 10 years, they’ll just say,“Oh you know, you can find someone else.” It was similar when my dad died because we were estranged. People would ask, “Were you close? And I’d say “no” and I got the feeling it was like ‘Oh, thank God, now I don't have to deal with her grief.’ Whereas my grief was just as meaningful. So I wanted to play with all of these different stories that our culture gives us and write a new story.

I was also thinking about why we have to make this conscious effort to give ourselves permission to feel the “in-between feelings,” the non-binary ones, as you say. Do you chalk that up to just the way our brains function or the narratives American culture feeds us?

I think it's 100% the society we live in. Our bodies are incredibly wise and tell us everything that matters to us. A feeling is just our bodies saying “this matters.” Our society tells us that some things matter and some things don't and that we should be so disembodied that certain emotions don't belong in our body. But we are all the owners of our bodies and any feeling should be welcome there. Humans are incredibly emotionally intuitive animals and we're capable of over 34,000 distinct emotions. It seems so obvious that those emotions would overlap and contradict themselves and that you can feel can feel so many things in one minute, but we have so many narratives that say, “if someone else is suffering more than you, you're not allowed to suffer,” or “you can't miss someone who hurt you.” I so badly want people to be as embodied as possible and let every feeling in. I also do think it’s very American. I heard from a neuroscientist that disembodiment is specific to contemporary American culture. Girls start to experience disembodiment around age 11—where they feel like certain feelings are allowed and certain ones aren't—and boys start experiencing it at age five or six. We have a big problem and I would love to help get people to be more receptive to their feelings.

I want to ask you not about disembodiment but dissociation. Do you ever feel disassociated from the moments that you describe and feel more present afterwards while recounting them? Or are you a fairly present person?

That’s such a good question, I love that. I was just thinking today, I'm a person who takes a long time processing things and a lot of people aren't that way. Many people can really identify exactly what's going on in the moment and I am someone who feels very compelled to mythologize the things that happened to me, meaning “what does this small story have to do with my big story?” And so I take a really long time to process. which is hard for someone who does a lot of self-expression on social media, because often the way that art is consumed these days if something in the news happens, or even something in my life happens, people will expect real-time reactions to that.

I was noticing earlier this year when I read lot of poetry about World War II, most of the poems were written about 10 years after the war, because people needed time to process. I just kept thinking that would not be allowed today. People want reactions so quickly. That’s another thing I hope to encourage: more processing time.

It’s so fascinating. The speed at which we can share now is supposed to measure up to the speed at which we can process and it just doesn’t. So before we started publishing work on Instagram and before your first book, how were you supporting yourself? Are you a full-time writer/illustrator now?

I am a full-time writer and I also work as a chaplain at a hospital. I've had every job you can think of. My most recent office job was marketing for a nonprofit, but I did all kinds of things. I've never been a big advocate for quitting your day job and taking a leap. I didn't do it until I got a book deal that sustained me for about a year. I always thought I'd go back to working and I'm doing that now--very happily so.

In another essay in the book, you describe the process of freezing your eggs as freeing because it allowed you to lower your expectations and stop dating from a place of scarcity. Did you see a shift in your dating life based on this action that you took?

I think I was able to approach dating with a bit more empowerment—and what I mean by that is to take some time off. I really needed a break from dating and I felt like that wasn't allowed because I was in my early 30s. There was this tremendous amount of time pressure that I felt and so to be able to say I'm going to take a proper year off from dating was really such a gift. I knew plenty of men who had done that and freezing my eggs did that for me. You don't have to freeze your eggs to give yourself a break, but for me that was kind of the permission, which was really beautiful.

You also also talked about this in an essay in the book: the guilt of not feeling creative when you know you are inherently creative. It’s a really tough feeling to carry. You seem to kind of surrender to that notion, or you say that you do, which is amazing. Do you often heed your own advice?

That is so funny. I was just talking to my friend about how she and I are so great at giving advice. No, I’m not great at it; I don't think anyone is great at taking their own advice. That theme came up for me in 2020 because I'm used to making art about really specific things that happen to me. I’ve always intuitively known that the more specific you are about your experience, the more universal it comes across. But this year was really tough, because everyone was kind of going through the same thing, so I felt like I didn’t have anything to share. Previously, I might have been going through a breakup, and maybe half the world was going through a breakup, but the other half wasn't, so I can kind of bring some insight. But in 2020, we were all going through this same thing and I didn’t have anything to add. Everything that could be said has already been said. I just felt like, ‘oh, man, my experience doesn't matter.’ I'm not going through the hardest thing. I'm not going through a really specific thing. So, I had to learn how to become creative in different ways and a lot of that was looking at old memories. But it was hard. I'm still kind of figuring out how do you talk to the world who just went through the same thing.